“Who TF Are You?” – Leo Dasilva Blasts Nigerians for Policing How People Should Mourn Their Loved One

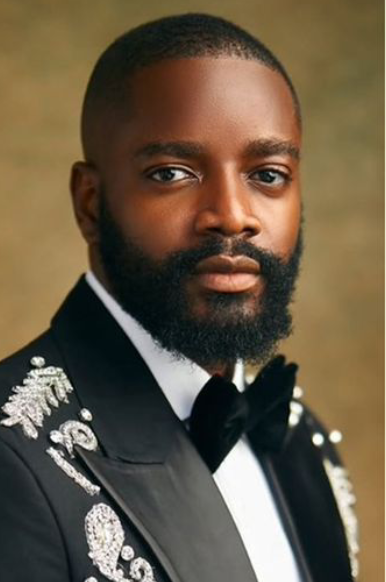

In the age of social media where grief, pain, and even moments of silence play out in the digital town square, the line between empathy and intrusion is becoming increasingly blurred. Former Big Brother Naija housemate and entrepreneur, Leo Dasilva, sparked a heated debate online after publicly slamming Nigerians who feel entitled to dictate how others should mourn the death of their loved ones. His sharp words, laced with frustration, cut through the noise of unsolicited opinions and pointed to a deeper issue in society: the culture of judgment that follows individuals even in their most vulnerable moments.

The conversation was triggered by the story of a widower abroad whose wife had just passed away, leaving him with three children to care for. Amid his grief, the man continued creating content online because that was his source of livelihood, the only way he could provide for his family. But Nigerians on social media quickly flooded his page with demands that he go offline to mourn, insisting that staying online was disrespectful to the memory of his wife. Leo Dasilva, never one to shy away from calling out hypocrisy, quickly intervened with a blunt rebuke. “Who tf are you to tell anyone what to do after they lose their loved one?” he tweeted, drawing a sharp line between compassion and control.

The clash of opinions revealed two contrasting realities. On one hand were those who argued that tradition, respect, and even optics required a grieving spouse to retreat from public life, take time off, and wear sorrow as a visible badge. On the other hand were those who, like Leo, insisted that grief is deeply personal, unique to each individual, and that no outsider, especially strangers on the internet, has the right to impose their version of mourning on someone who is just trying to survive. “Nobody's truth except the person mourning is valid,” Leo asserted, emphasizing that unless one is inside the pain, experiencing the loss firsthand, their judgment is irrelevant and often harmful.

This argument resonates with the reality many Nigerians know too well: people who never contribute financially or emotionally to a burial are often the loudest voices dictating how the bereaved should grieve. One user, @dollamanhenry, shared his own painful experience, recalling how after losing his wife three years ago, people criticized him for continuing to post about his business online. They called it insensitive, yet not a single one of those critics contributed “a kobo” toward the coffin or funeral expenses. His story laid bare the hollowness of social commentary that thrives on moral policing without any real support for the grieving.

Another example came from Afrozollo, who narrated how a friend lost his father and, in the middle of the burial, picked up a phone call. Observers muttered in disapproval, asking how a man could answer calls while his father was being laid to rest. But the call turned out to be from the deceased’s own brother, who was trying to confirm the location of the event. It was a reminder that life does not freeze entirely for mourning, and sometimes practicality overrides societal expectations of what grief should look like.

Leo’s criticism struck a chord because it peeled back the hypocrisy of a culture that is quick to prescribe how others should handle their pain while ignoring the realities that surround loss. In Nigeria and many parts of Africa, mourning is traditionally a communal affair with elaborate rituals, extended periods of withdrawal, and visible expressions of sorrow. But in a globalized world where survival often hinges on work that is public, digital, and constant, those traditions are colliding with new realities. The widower abroad, whose story sparked the debate, simply could not afford to disappear offline when his online presence was the only source of income for him and his children. For him, grief and survival coexisted, and shutting down his livelihood would only compound the tragedy.

Leo’s response—sharp, emotional, and unapologetic—highlighted the importance of respecting individual grief journeys. By asking the blunt question “Who tf are you?” he challenged Nigerians to confront their tendency to enforce uniform standards of behavior even in the most intimate of circumstances. His words exposed the judgmental streak often disguised as cultural values or communal concern, which too often robs people of the right to grieve authentically.

The debate that followed was intense, with some agreeing that his point was valid but still insisting that cultural respect demanded a period of visible mourning. One user, @elhadj_pablo, tried to strike a balance, saying, “Asking him to go offline to mourn isn’t too much and yes his point is valid. Two truths can coexist.” But Leo was quick to reject the idea, doubling down that no truth except that of the person mourning matters. “Please come off it. We do not know the agreement he and his wife had. Why would anyone tell him what he should do? It’s no one’s place. Especially strangers.”

His response sparked reflection on how much of grief is shaped by perception rather than personal experience. Too often, people worry about how their mourning will be seen rather than how they are truly coping. Families are judged if they celebrate birthdays or weddings soon after a funeral, widows are scrutinized if they smile too quickly after losing a husband, and breadwinners are criticized for resuming work because society equates prolonged visible suffering with respect. In reality, grief is not a performance, and pretending to hurt in ways that align with public expectations often deepens private pain.

What made Leo’s statement particularly powerful was his defense of autonomy. He reminded Nigerians that no outsider has the right to dictate grief. Every relationship is different, every loss carries its own weight, and every person must find their own way to move forward. For some, that means going offline and shutting out the world, while for others, it means continuing with the routines that provide stability, income, or even distraction from overwhelming sorrow.

His tweets also exposed the harshness of social media where judgment comes cheap but compassion is rare. People who type out long criticisms about how someone should behave in mourning often fail to send real support—no financial help, no physical presence, no emotional comfort. They demand withdrawal from online spaces without recognizing that for many, especially those abroad or working in digital economies, the online world is not just entertainment but survival.

Ultimately, Leo Dasilva’s outburst was not just about defending a stranger abroad but about reclaiming the right of every grieving person to choose their path without fear of condemnation. His raw words, “Who tf are you?” echoed like a reminder to society that grief is not communal theater but an individual battle, often fought in silence, often misunderstood, and always deeply personal. His stance challenges Nigerians to rethink the culture of prescribing sorrow and instead embrace empathy without control, support without judgment, and silence without interference.

In a society that too often places appearances above realities, Leo’s voice rings out as a call for honesty and compassion. Grief is messy, unpredictable, and unique. It does not come with a manual, and it certainly does not need an audience dictating the script.