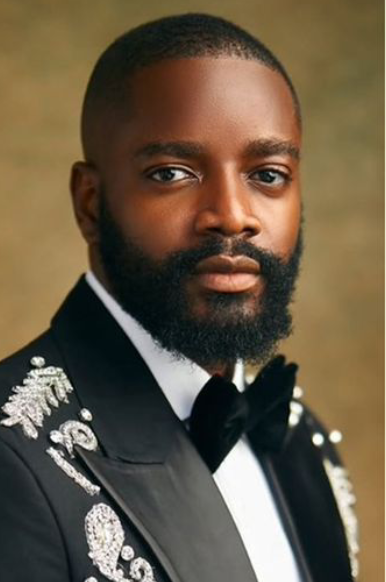

“Start in Your Region Before You Shout Revolution” – Seyi Law Warns Nigerians Over Nepal-Style Protest Excitement

Comedian and social commentator Seyi Law has sparked intense debate across Nigerian social media after issuing a stern warning to citizens who have been hailing the ongoing Nepal protest as a blueprint for Nigeria’s liberation. In a strongly worded post, the comedian cautioned Nigerians against being carried away by the excitement of a foreign struggle without weighing the consequences that follow when chaos is unleashed in one’s own backyard. His message was simple but biting: “Remember to start in your region.”

The post quickly gained traction as Nigerians debated whether Seyi Law was making sense or simply sounding like another celebrity who prefers caution over confrontation. He highlighted the immediate aftermath of Nepal’s nationwide protests, which saw widespread destruction, jailbreaks, looting, and violence against women. According to him, the same Nigerians applauding from afar would turn to regret if similar unrest took place within the country. “They are happy about Nepal until rebuilding becomes a problem. They will never learn from Libya,” Seyi Law wrote.

His mention of Libya drew strong reactions because of the infamous 2011 revolution that toppled Muammar Gaddafi but left the North African nation in ruins, plagued with militia wars, a collapsed economy, and ongoing instability. For Seyi Law, the pattern is clear: revolutions are often glorified at the peak of the chaos, but when the dust settles, citizens are left to deal with regrets, destruction, and a weakened society while politicians escape largely unscathed. He pointed out that the masses often cheer at images of burnt buildings, vandalized landmarks, and freed criminals in the heat of protest, only to realize later that they have destroyed their own communities, weakened their safety nets, and unleashed forces they cannot control.

The comedian went further, drawing attention to the reports coming out of Nepal, where protesters initially set out to demand systemic change and accountability. However, according to him, those same protests have already been hijacked by criminal elements who have used the chaos as cover to loot, assault, and destroy. “They will show you burnt buildings and politicians beaten, but they won’t tell you that Nepaleses are regretting now. Iconic structures have been destroyed, criminals escaped, women raped and their properties looted. They’re already claiming the protest was hijacked,” he warned.

Seyi Law’s message is not simply about Nepal but also about Nigeria’s recurring flirtation with mass protests. Since the historic #EndSARS demonstrations of 2020, Nigerians have debated whether another mass uprising is the only way to force politicians into genuine reform. However, the scars of #EndSARS still remain fresh: dozens of lives lost, properties damaged, widespread crackdowns, and a divided memory of what was supposed to be a turning point for the nation. For some Nigerians, the memory of Lekki Toll Gate and the government’s handling of the protest is a reason to never risk that path again. For others, it is evidence that only sustained revolution can break the cycle of corruption and bad leadership.

But Seyi Law’s warning comes as a cautionary tale: excitement about foreign revolutions must be balanced with the sobering realities that often follow. “Keep fanning what you can’t sustain and remember to start in your region,” he said, throwing the responsibility back at those quick to call for nationwide upheaval. His suggestion to “start in your region” seemed to be a subtle reminder that many Nigerians often cheer for nationwide action while refusing to take accountability for problems within their own localities.

The reaction to his post was polarized. Some Nigerians praised him for speaking hard truths, noting that revolutions rarely leave countries better than they were before. “He’s right. Revolution looks sweet on camera until you’re queuing for food with no infrastructure left,” one commenter said. Another wrote: “People don’t understand that after burning down your schools, hospitals, and government offices, you are the one who suffers. Politicians can always rebuild for themselves.”

Others, however, criticized Seyi Law, accusing him of fearmongering and siding with politicians. “This is how Nigerian celebrities always discourage the people. They benefit from the system and then turn around to tell us to endure oppression,” one critic fired back. Another added: “If we always think about the aftermath, we’ll never demand change. Nepal is trying; at least they are standing up to their leaders. Nigerians are too comfortable with suffering.”

The debate reflects Nigeria’s larger dilemma: citizens want change but fear the cost of demanding it. The political elite have proven resilient, surviving multiple waves of anger while ordinary Nigerians bear the brunt of inflation, insecurity, unemployment, and failing infrastructure. Yet, each time calls for protest arise, voices like Seyi Law’s emerge to caution against the dangers of spiraling unrest.

His statement also sparked a historical reflection online. Many Nigerians recalled Libya’s descent into chaos after Gaddafi’s fall, Sudan’s bloody revolution that gave way to military coups, and even the Arab Spring in Egypt which saw initial euphoria but ultimately returned the country to military-backed rule. Critics of revolution argue that Africa’s fragile democracies and institutions rarely survive such shocks, often leaving citizens worse off.

But despite the warnings, the underlying frustration among Nigerians remains palpable. The economy is biting harder, food prices continue to skyrocket, insecurity threatens lives across regions, and citizens feel abandoned by leaders who appear insulated from suffering. To many, the idea of revolution is not just exciting but necessary. However, voices like Seyi Law’s force them to grapple with the hard question: what happens after the fire burns?

The comedian concluded his message with a stark proverb: “Like Gehgeh, had I know is the last comment of a fool.” In essence, he urged Nigerians to consider carefully before chasing foreign models of protest, reminding them that regret often comes too late, when damage has already been done. His words may not stop the yearning for radical change, but they highlight the uncomfortable truth that revolutions are easier to start than to finish.

For now, the online battle of ideas rages on: some say Nigerians must rise like Nepal and shake off the chains of oppression once and for all, while others argue that the risks are too high and the aftermath too unpredictable. Whether Nigerians choose to heed Seyi Law’s advice or ignore it, one thing is certain—anger against the system is building, and if history is anything to go by, it only takes one spark to set the country ablaze.