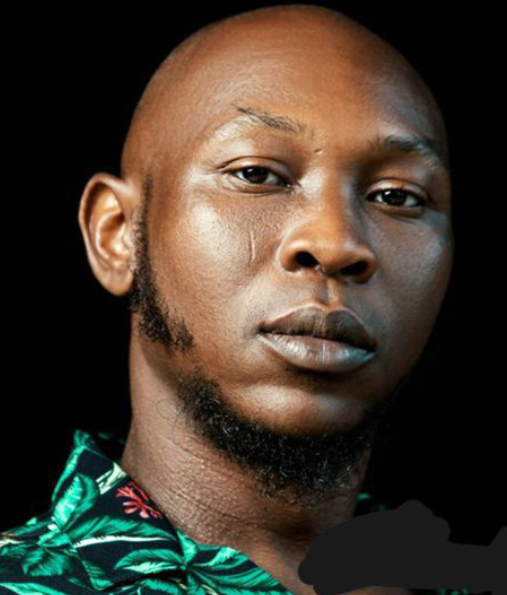

Seun Kuti Slams Yoruba Monarchs: '90 Percent Don’t Believe in Yoruba Gods'

In a fiery statement that has sparked widespread conversation online and off, Nigerian musician and activist Seun Kuti has publicly criticized Yoruba traditional rulers, accusing the majority of them of hypocrisy and cultural betrayal. In a bold social media post shared via his @bigbirdkutio handle, the Afrobeat artist did not mince words as he declared, “90 percent of Yoruba kings don't believe in Yoruba gods yet they sit on Yoruba thrones and make a mockery of what it means to be Yoruba.” The statement, terse and forceful, has struck a nerve across the Nigerian cultural and political landscape.

Kuti’s comments arrive at a time when questions about authenticity, tradition, and leadership are gaining renewed traction in the national discourse. As a son of the late Afrobeat pioneer and political icon Fela Kuti, Seun has never shied away from social commentary, but his latest message targets an institution deeply entrenched in both Yoruba identity and Nigeria's wider historical fabric—the monarchy. His words suggest not just disappointment, but a fundamental disillusionment with what he sees as a performative version of Yoruba culture that has been stripped of its spiritual roots.

In his Instagram post, which reads more like a poetic manifesto than a typical celebrity rant, Kuti paints a picture of cognitive dissonance between Yoruba tradition and the modern behavior of many who claim to uphold it. “Fanfare in the midst of misery. Joy in the face of poverty. And glamor in the presence of ignorance,” he writes, using rhythm and contrast to highlight what he sees as a disturbing trend among Yoruba monarchs: a fixation on celebration and image, while real societal issues fester beneath the surface. According to Kuti, the problem isn’t just religious, but existential—it’s about the erosion of identity and the commodification of culture for spectacle rather than substance.

Kuti’s assertion that Yoruba kings no longer believe in the gods of their ancestors implies a deep schism between form and faith. The Yoruba traditional system, rooted in centuries of history and spirituality, intertwines kingship with divine ordination. The Oba, or king, is traditionally seen not just as a political leader but as a spiritual figure—a representative of the deities, chosen by Ifá divination and bound by ritual duties. If that belief has eroded, as Kuti claims, then the very foundation of Yoruba kingship may be under silent collapse.

While many traditional rulers continue to wear their beaded crowns and host elaborate festivals, Kuti questions whether these displays are still authentic or merely hollow rituals performed for applause. His criticism goes beyond personal belief and dives into the ethical implications of cultural representation. “Being Yoruba is not a festival!” he insists, warning against reducing an ancient and complex identity to superficial performances devoid of meaning or commitment.

Perhaps the most provocative line from his post comes at the end: “There is no bigger criminal than the benevolent king/dictator.” With this statement, Kuti places monarchy under the same scrutiny as corrupt political leadership, suggesting that the charm of benevolence is often used to mask authoritarian tendencies or cultural exploitation. It’s a loaded accusation, especially considering the reverence still afforded to traditional rulers in many parts of Yoruba land. But to Kuti, reverence without accountability is just another tool of oppression.

The musician’s stance has drawn mixed reactions. Some applaud his courage in calling out what they too see as a growing disconnect between Yoruba tradition and its custodians. Others have criticized his tone, arguing that belief systems are personal and that Yoruba kings, like anyone else, are entitled to evolve spiritually. Some commenters have also pointed out that many Yoruba monarchs still actively uphold traditional rites and support indigenous religions, questioning the legitimacy of Kuti’s sweeping “90 percent” claim.

Still, Seun Kuti's post fits squarely within a broader conversation about authenticity and postcolonial identity. Across Africa, and particularly in Nigeria, cultural institutions are grappling with how to maintain relevance in a rapidly modernizing world. The tension between ancestral tradition and contemporary belief systems—especially in a country with significant Christian and Muslim populations—raises difficult questions about what cultural preservation really means. Is tradition defined by form, or by faith? Is a king still a king if he no longer believes in the gods that once legitimized his rule?

Seun Kuti’s critique also echoes a larger generational frustration with what many see as the failure of both traditional and modern leadership in Nigeria. From endemic corruption to youth unemployment and systemic poverty, the promise of post-independence prosperity has remained elusive. Against this backdrop, Kuti’s scathing analysis of Yoruba royalty feels less like an isolated cultural critique and more like part of a broader indictment of Nigerian leadership at every level.

In true Afrobeat tradition, Kuti’s words function not just as commentary but as confrontation. His use of artful language and sharp metaphor reflects the legacy of his father, whose music was a weapon against tyranny and whose life was dedicated to challenging power structures. But unlike his father’s blistering saxophone solos and hypnotic grooves, Seun’s medium of resistance today is digital—his battleground, social media. In just a few lines, he’s managed to ignite a conversation that stretches from palace courtyards to Twitter timelines, from shrines to radio shows.

Whether one agrees with Seun Kuti or not, his message forces a reckoning with uncomfortable questions: What does it mean to sit on a throne that one no longer spiritually respects? What happens when symbols outlast their meanings? And who really gets to define what it means to be Yoruba in the 21st century?

For now, Kuti’s post remains online, gaining traction and provoking debate. In a time when silence is often easier than honesty, his decision to speak out—bluntly, poetically, and without compromise—demands attention. Whether it will lead to introspection or just indignation remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: Seun Kuti has once again used his voice not to entertain, but to awaken.