“If You Can’t Protect Us, Let Us Protect Ourselves”: Rhodes-Vivour’s Explosive Call Forces National Debate on Firearm Licensing

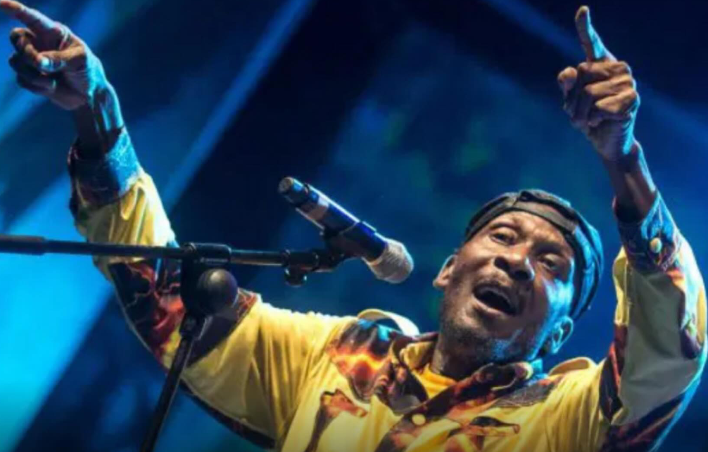

Nigeria’s already heated national security discourse erupted into fresh controversy on Monday after Gbadebo Rhodes-Vivour (GRV), the Labour Party’s 2023 Lagos governorship candidate, delivered one of the most provocative political statements of the year. Speaking during an interview on Channels Television’s The Morning Brief, Rhodes-Vivour declared that if the federal government cannot protect Nigerians, it should begin considering the licensing of firearms for citizens — a statement that has sparked intense reactions across the country.

The comment came amid escalating insecurity and a troubling spike in violent incidents, including the recent abductions in Kwara and Ogun States that have reignited public fears. For many Nigerians, the situation has begun to feel eerily familiar, with the cycles of kidnapping, terror threats, rural banditry, and attacks on communities blurring into a constant state of anxiety. GRV’s message, bold and unfiltered, seemed to capture what many citizens whisper privately but rarely voice publicly: that trust in the Nigerian state is thinning to dangerous levels.

During the interview, Rhodes-Vivour painted a grim picture of Nigeria’s institutional decay, arguing that the erosion of trust in public institutions is pushing the population toward desperation. “Destruction of institutions and loss of public trust make people lose hope in government,” he said, noting that when citizens feel they cannot rely on the judiciary, police, or military, a dangerous vacuum emerges. According to him, that vacuum compels people to look for ways to survive on their own — even if that means arming themselves for protection.

He referenced familiar examples that highlight the Nigerian population’s long-standing pattern of self-reliance. Nigerians have created alternatives for power supply through generators and solar systems after decades of failed power reforms. Communities have drilled boreholes to replace unreliable water boards. Homeowners and estates have hired private security where state policing proves ineffective. For Rhodes-Vivour, these examples point to a simple but chilling conclusion: when institutions fail consistently, citizens become their own fallback plan.

“The idea of governance is that we give up our rights so the government can protect lives,” he stressed. “If the government fails, people must take action themselves.” That action, according to him, might one day include self-defense measures, especially if terrorists continue to strike while the government appears unprepared or reactive. His warning was directed not only at policymakers but also at a political elite he accused of engaging in performative governance rather than operational, results-driven security management.

The turning point of the conversation came when Rhodes-Vivour addressed a controversial statement attributed to former U.S. President Donald Trump. Trump had warned that he might intervene in Nigeria “guns-a-blazing” against Islamic terrorists — a remark that has already sparked diplomatic chatter and domestic outrage. But GRV took the statement as a wake-up call, arguing that it symbolized a collapse of global confidence in Nigeria’s leadership. “It is an absolute disgrace that a foreign president had to make this statement for our leaders to sit up,” he said, calling the situation a national embarrassment.

His comments reframed the issue beyond political rivalry or ideological divide, touching instead on national dignity and international perception. For Rhodes-Vivour, the fact that such a warning could be publicly issued at all — no matter how theatrical Trump’s rhetoric can be — highlights the severity of Nigeria’s internal crisis and the weakness of its current response systems. “Nigeria has the potential to protect itself, and we should not depend on someone else to save us,” he insisted.

Rhodes-Vivour further criticized what he described as a “performance-driven culture” in Nigerian governance, where symbolic actions substitute real strategy. He called for genuine accountability for the military and intelligence agencies, improved equipment for troops at the frontlines, better surveillance mechanisms, and direct disruption of terrorist supply chains. He argued that any government that fails to prioritize those measures should not expect citizens to remain defenseless.

Security analysts say GRV’s comments reflect a growing sentiment among Nigerians who feel cornered by insecurity. Over the years, calls for state police, community defense groups, and structured civilian militias have gained traction, especially in zones most affected by banditry and terrorism. Some commentators believe that Rhodes-Vivour’s suggestion is an extension of that long-running debate — though one that enters far more dangerous territory given Nigeria’s diverse population and already high rate of unregistered weapons.

Still, for others, his words represent a legitimate expression of frustration in a country where citizens often feel like soft targets. The argument is that Nigeria’s size, terrain, and demographic complexity demand more robust, innovative, and decentralized approaches to the security question. Firearm licensing, to them, is not an invitation to chaos but a structured pathway to responsible self-defense, especially if anchored by strict regulations, psychological evaluations, training requirements, and digital tracking systems.

However, critics warn that firearm licensing may worsen Nigeria’s already volatile security environment. They fear it could open the floodgates to widespread misuse, accidental shootings, ethnic tension, electoral violence, and criminal opportunism. Many believe GRV’s suggestion, though well-intentioned, raises serious questions about national readiness for such a transition. Nigeria’s current challenge, they argue, is not the absence of weapons, but the absence of order, accountability, and effective security management.

But even those opposed to firearm licensing acknowledge that Rhodes-Vivour’s statement illuminates a more profound truth: Nigerians are losing faith in traditional systems of protection. When citizens begin to publicly discuss arming themselves, it signals not just frustration but a psychological tipping point. And once trust erodes to that degree, rebuilding it becomes a monumental task.

For now, Rhodes-Vivour’s comments have thrust the national security conversation into a new phase. Whether seen as a call to action, a political provocation, or a reflection of reality, his message is resonating widely because it echoes a sentiment many Nigerians feel daily — that they are living in a country where survival often rests on individual resilience rather than state capacity.

The coming days will likely bring rebuttals from government officials, clarifications from security agencies, and heated debates on social media. But one thing remains clear: GRV has touched a nerve. His words, delivered in a calm studio setting, have found their way into Nigeria’s broader struggle with insecurity — a struggle that continues to define the national mood, test the limits of governance, and shape the future of public trust.

And until the government can restore safety and confidence, the question he raised will continue to echo loudly: If the state cannot protect its people, what alternative do they truly have?