“We Can’t Keep the Uneducated Leading the Educated” – Jude Okoye Sparks Heated Debate Over Electoral Reform in Nigeria

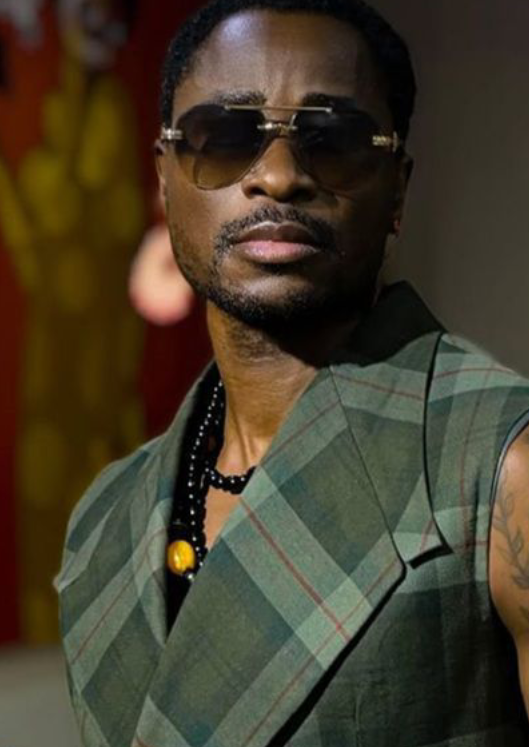

Nigerian music executive Jude Okoye has stirred a storm of national discourse after voicing a controversial opinion on Nigeria’s political system, urging lawmakers and citizens alike to prioritize educational reform within the electoral process. In a bold and unapologetic social media post, the well-known talent manager and elder brother to award-winning singer Peter and Paul Okoye (P-Square) declared, “We can’t have the uneducated leading the educated. Makes zero sense.” His remarks, which call for at least a university bachelor’s degree as a baseline qualification for political office, have since gone viral, igniting passionate responses across social and traditional media platforms.

Jude Okoye, who rarely comments on political affairs, took to X (formerly Twitter) with a clear and pointed message: “How hard is it to reform our electoral act making at least a Uni bachelor’s degree a benchmark for qualification to run for any office in Nigeria?” Accompanied by the hashtags #ElectoralReform and #NAS (an apparent reference to the National Assembly), his post immediately caught fire, triggering an avalanche of reactions from celebrities, academics, political analysts, and everyday Nigerians grappling with the harsh realities of governance in the country.

In a nation where access to quality education remains deeply unequal, and where political offices have historically been occupied by individuals with questionable academic credentials, Okoye’s statement did more than just provoke — it exposed a painful contradiction in the Nigerian political landscape. Many have echoed his sentiments, arguing that educational attainment should be a basic prerequisite for leadership roles, especially in a complex 21st-century economy. Supporters of the idea point to the need for leaders who can grasp policy intricacies, engage in global discourse, and formulate intelligent strategies that benefit the masses.

On the flip side, critics have labeled Okoye’s position as elitist and disconnected from Nigeria’s socio-political history. Detractors argue that some of the most impactful leaders across the world, including in Africa, have not necessarily held college degrees. They also highlight the danger of excluding vast portions of the population — including grassroots community leaders and traditional politicians — who may not have had the opportunity to attend a university, yet possess significant wisdom, influence, and leadership experience. Many believe that good leadership requires integrity, vision, empathy, and the will to serve — traits that aren’t exclusive to university graduates.

Nonetheless, Okoye’s argument arrives at a moment when Nigerians are increasingly frustrated with a political class perceived as out of touch, corrupt, and inept. From economic mismanagement to rising insecurity and poor infrastructure, there’s a growing hunger for transformative leadership — leadership that can think critically, adapt to the modern world, and deliver on the promise of democracy. In that context, the push for a more educated political class may resonate strongly with Nigeria’s burgeoning youth population, most of whom are university-educated and technologically savvy.

The debate is further intensified by Nigeria’s long history of controversial educational records among politicians. Allegations of forged certificates, questionable qualifications, and academic fraud have plagued several high-profile political figures, casting doubt on the credibility of leaders at all levels. The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), responsible for vetting candidates’ credentials, has faced numerous legal battles over candidate qualifications, some of which have reached the Supreme Court. This makes Okoye’s plea for reform not only timely but necessary for a political system long overdue for structural overhaul.

Interestingly, the Nigerian Constitution does not require a university degree to contest for most public offices. For the presidency, governorship, senate, and house of representatives, the law currently stipulates a “school leaving certificate” or its equivalent — a requirement many view as outdated and insufficient. Okoye’s call for a revised benchmark aligns with broader demands for constitutional amendments aimed at aligning leadership standards with global best practices.

Some political observers suggest that the real challenge is not merely in academic qualifications but in ethical orientation and competence. Nigeria’s experience with highly educated yet morally bankrupt politicians has left many skeptical about academic titles as a sufficient safeguard against corruption and poor governance. The country needs not just educated leaders but visionary reformers committed to transparency, inclusiveness, and service.

Reactions from the entertainment industry have been largely supportive of Okoye’s stance. Celebrities such as Banky W, who himself contested for office, and Falz the Bahd Guy, known for his political activism, have in the past expressed similar frustrations about the quality of political leadership in Nigeria. This increasing political consciousness among Nigerian entertainers signals a shift from passive commentary to active civic engagement, and Okoye’s remarks may well galvanize a new wave of advocacy for electoral reform within and beyond the creative industry.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt, ordinary Nigerians are weighing in. A 26-year-old graduate of the University of Benin, Joy Ibe, said, “Jude is 100% right. You can’t lead people when you can’t even write a proper speech. We need leaders who understand policies, economy, law — not people who can barely read.” Others, like 45-year-old mechanic Musa Danjuma in Kano, disagree. “I no go school, but I sabi correct person wey get sense. Some people wey go university no even fit manage pure water business,” he retorted.

Ultimately, Jude Okoye’s statement, while simple on the surface, taps into a deeper national conversation about what kind of leadership Nigeria truly needs moving forward. With the 2027 elections slowly drawing near, political analysts predict that issues of candidate qualification — including academic credentials — will increasingly feature in public discourse and legislative deliberation.

The National Assembly has been largely silent on the matter for now, but civil society groups are already taking cues. Calls are growing for constitutional amendments, public petitions, and policy think tanks to develop frameworks for a more educated, efficient, and credible political class. Whether this results in real change remains to be seen, but one thing is clear: Jude Okoye’s statement has hit a nerve, and the conversation it has sparked is not going away anytime soon.

As Nigeria continues to navigate its democratic journey, the question lingers in the minds of millions: should educational qualifications be the gatekeeper to political leadership, or should the gates remain open to all — regardless of academic background — as long as they can win the hearts of the people? Only time, and perhaps the courage to reform, will tell.