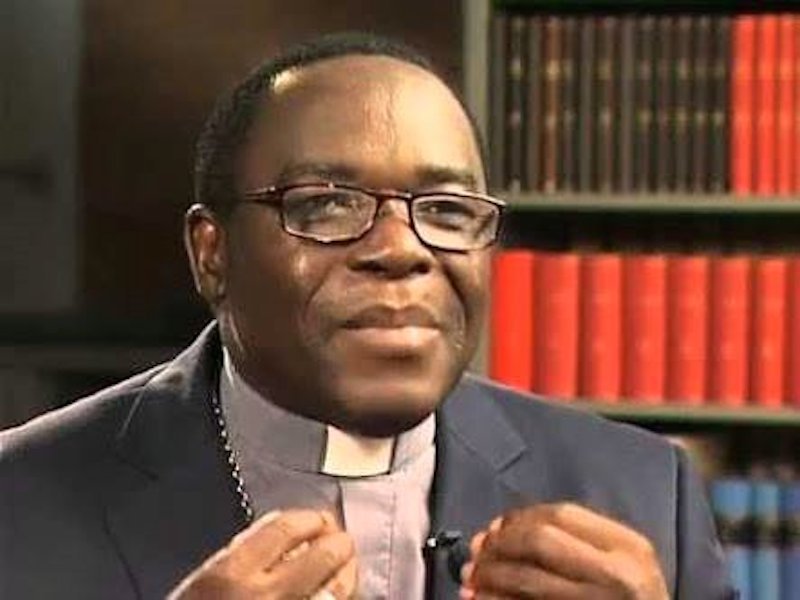

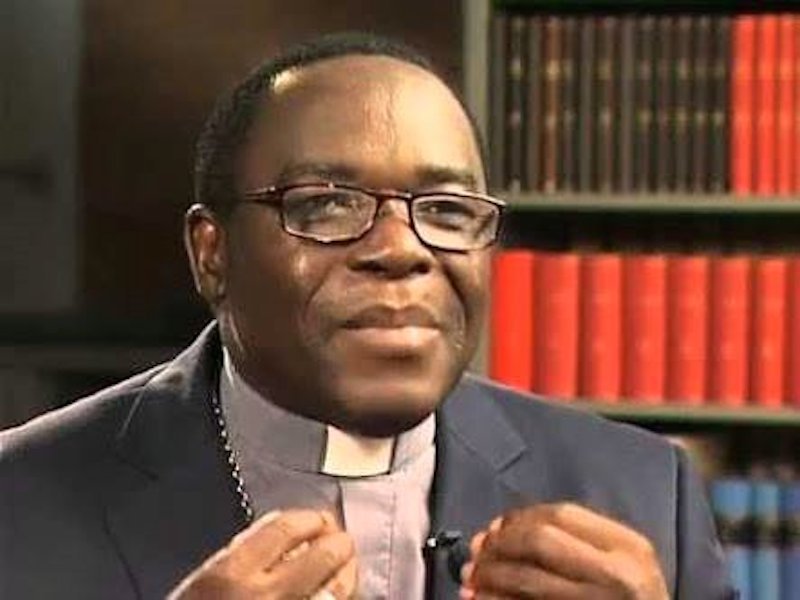

In a world already burdened by conflicts and mistrust, few figures in Nigeria’s religious and political landscape ignite debate as fiercely as Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah. The Catholic Bishop of Sokoto Diocese recently made headlines for urging the United States not to re-designate Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern over religious freedom violations — a decision that has drawn both admiration and outrage in equal measure.

Speaking at the launch of the Aid to the Church in Need (ACIN) 2025 World Report on Religious Freedom in the World held at the Augustinianum Hall in Vatican City, Bishop Kukah argued that such a move by the U.S. would “hurt ongoing efforts” to promote dialogue, national healing, and interfaith understanding under the Bola Tinubu administration.

Kukah, known for his eloquence and sometimes controversial interventions in national discourse, said Nigeria, while still ravaged by violence, discrimination, and insecurity, is beginning to show “encouraging signs of progress that should be strengthened, not punished.” In his words, “Re-designating Nigeria a Country of Concern will only make our work in the area of dialogue among religious leaders even harder. It will increase tensions, sow doubt, open windows of suspicion and fear, and simply allow the criminals and perpetrators of violence to exploit. What Nigeria needs now is vigilance and partnership, not punishment.”

The statement, credited to Punch, has since rippled through both local and international communities — especially among persecuted Christians who feel abandoned by the very leaders meant to defend them. To many, Kukah’s plea to Washington reads like a polished diplomatic defense of a system that has consistently failed to protect its most vulnerable.

But there’s a deeper sentiment stirring beneath the surface — one that speaks to the growing frustration among Nigeria’s faithful who perceive an undercurrent of betrayal from their own. Critics argue that Kukah’s position, while cloaked in calls for “dialogue and healing,” inadvertently shields the government from international accountability. The notion that external pressure “hurts progress” has long been used by regimes to buy time, even as citizens continue to bleed under the weight of terror and targeted killings.

Across the Middle Belt and Northern regions, countless families have been displaced by relentless attacks — often underreported, rarely investigated, and almost never punished. For those communities, appeals for leniency toward the Nigerian government sound more like abandonment than advocacy.

There’s an old truth about oppression: no persecution thrives without the silence or complicity of a few among the oppressed. From the high pulpits to the corridors of political power, the Nigerian Christian landscape has witnessed its fair share of such betrayals. The so-called “men of God” who once thundered against injustice now speak in whispers, and some have traded their prophetic voices for political convenience.

Yet, hope lingers. A growing network of Nigerian Christians abroad continues to amplify the voices of victims, lobby international bodies, and fund rescue operations across dangerous zones. Their advocacy has kept global attention from fading entirely. And perhaps that’s the irony of The Kukah Effect — even as it stirs division at home, it fuels resilience elsewhere.

In the end, history will judge not by the titles worn or the pulpits commanded, but by the courage shown when silence was convenient. Nigeria stands at a moral crossroads, torn between faith and fear, between truth and diplomacy. As one commenter aptly put it online, “Every genocide needs a Judas, but thank God help has risen from abroad.”

Whatever side of the argument one takes, the message remains clear — the world is watching, the oppressed are speaking, and the Church must decide where it truly stands.

— Busterblog.com