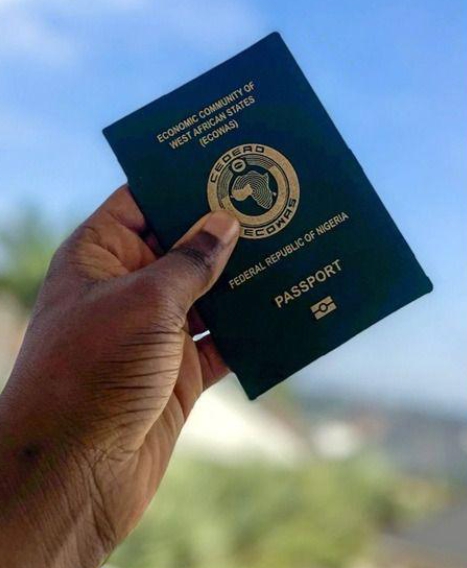

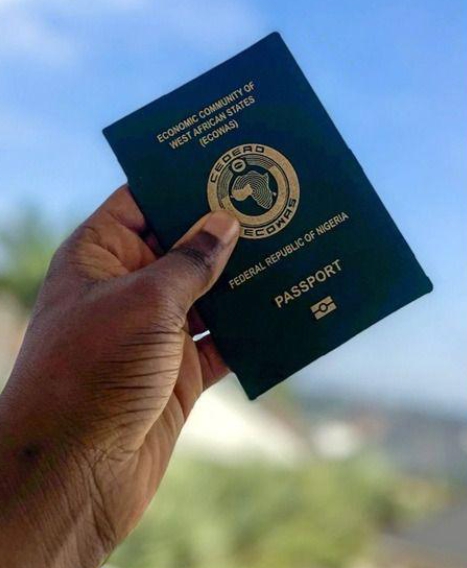

Married But Stateless: Foreign Husbands of Nigerian Women Cry Out Over Harsh Immigration Hurdles

A growing number of foreign men legally married to Nigerian women have taken to social media to reveal the immense and often demoralizing struggle they face in acquiring permanent residency or citizenship in Nigeria—despite living in the country for over a decade, raising Nigerian children, and actively contributing to society.

This wave of discontent was triggered by a post from Nigerian entrepreneur, Oluyomi Ojo, who highlighted the plight of his friend, a fellow African national who has lived in Nigeria for nearly 15 years. According to Ojo, this individual, despite being married to a Nigerian woman and raising a family in Nigeria, has been unable to secure permanent residency or citizenship. “He had to renew his papers periodically because Nigerian women are not allowed to petition for their spouses,” Ojo wrote in a tweet that has since garnered widespread attention and sparked national debate.

The immigration challenges described are not isolated incidents. Kwame Senou, another affected foreign husband, echoed a similar sentiment. "I am in the same situation. Even after 10 years, police still threaten me. Immigration, even with all the documents, at land border still ask for money," Senou lamented, painting a troubling picture of a bureaucratic system that not only fails to recognize their marital rights but also allegedly extorts them despite legal compliance.

Under Nigerian law, the immigration pathway for foreign spouses differs drastically based on gender. While Nigerian men can apply for citizenship or permanent residency for their foreign wives with relative ease, the reverse is not the case. Nigerian women, even when legally married, are not allowed to sponsor their foreign husbands for citizenship or residency. This legal discrepancy has left countless families in limbo, trapped in a system that penalizes them for a gender-based legal inequality that many describe as archaic and discriminatory.

In the global context, most nations offer a pathway—however stringent—for foreign spouses of citizens to naturalize over time. In many countries, after a few years of marriage and residence, spouses can apply for permanent residency or even citizenship. But in Nigeria, the pathway is not only blocked but legally nonexistent for foreign men married to Nigerian women.

This legislative oversight has far-reaching implications. Families face insecurity and constant fear. Children of these unions, who are Nigerian by birth, live in households where one parent is always at risk of deportation or harassment. These foreign husbands cannot fully participate in the economy—they are unable to access loans, own property with peace of mind, or even travel freely without facing humiliating questions at checkpoints or airports. Some have reportedly faced intimidation, illegal detention, and exploitation by immigration officers who allegedly exploit their vulnerable status for bribes.

Legal experts have also weighed in on the issue. Barrister Ifeoma Okoye, a human rights attorney based in Lagos, expressed outrage over the disparity. “It’s a clear violation of the principle of equality under the law. The Nigerian Constitution does not support discrimination based on gender, yet in practice, immigration laws clearly discriminate against Nigerian women who marry foreigners,” she said. Okoye further called for an urgent amendment to Nigeria’s immigration framework, pointing out that the existing laws reinforce gender inequality and subject families to unnecessary hardship.

Several social commentators and activists have now joined the call for reform. Advocacy groups for women's rights in Nigeria say the law reflects a deeper societal issue—an outdated mindset that assumes only men should be heads of households and therefore, only they should have the legal capacity to ‘bring in’ spouses. They argue that modern Nigeria, with its progressive voices and democratic structure, should not continue to enforce a policy that effectively treats its female citizens as second-class.

The frustration among affected men is not limited to legal documents. Many feel rejected by the very country they’ve chosen to make home. They contribute to the economy, pay taxes, and participate in community development. Some have invested in Nigerian businesses, raised children here, and even speak local languages fluently. Yet, the door to legal belonging remains firmly shut.

“I came here out of love, not just for my wife but for this country,” says Jean-Pierre, a Cameroonian who has been in Nigeria for 12 years with his Yoruba wife and three children. “But every year, I am reminded that I am not welcome. I spend money renewing permits, visiting immigration offices, getting harassed. What more must I do to belong?”

For now, there seems to be no clear path forward for these men. The silence from government authorities on the matter has been deafening. Attempts by journalists to contact the Nigeria Immigration Service for official comment have gone unanswered. Meanwhile, the families at the center of this crisis continue to live in uncertainty.

As social media continues to amplify their voices, there is hope that sustained pressure could spark legislative review. Several lawmakers have previously introduced motions to reform gender-based disparities in Nigeria’s legal system, but progress has been slow and often met with cultural resistance.

This issue underscores a larger question about national identity, family unity, and legal fairness in the Nigerian system. Should love across borders be punished? Should Nigerian women be penalized by their own country for choosing a foreign partner? These are the questions now gaining momentum in public discourse, and the answers may shape the future of many families.

Until Nigeria takes deliberate steps to amend these archaic immigration laws, thousands of families will remain trapped in a vicious cycle of fear, vulnerability, and bureaucratic oppression. For a country that prides itself on family values and hospitality, the time has come to live up to those ideals—not just in words, but in law.